Death to the World: What the Punk-to-Monk Pipeline Can Teach Us About Convert Culture

ROBERT CADY SALER

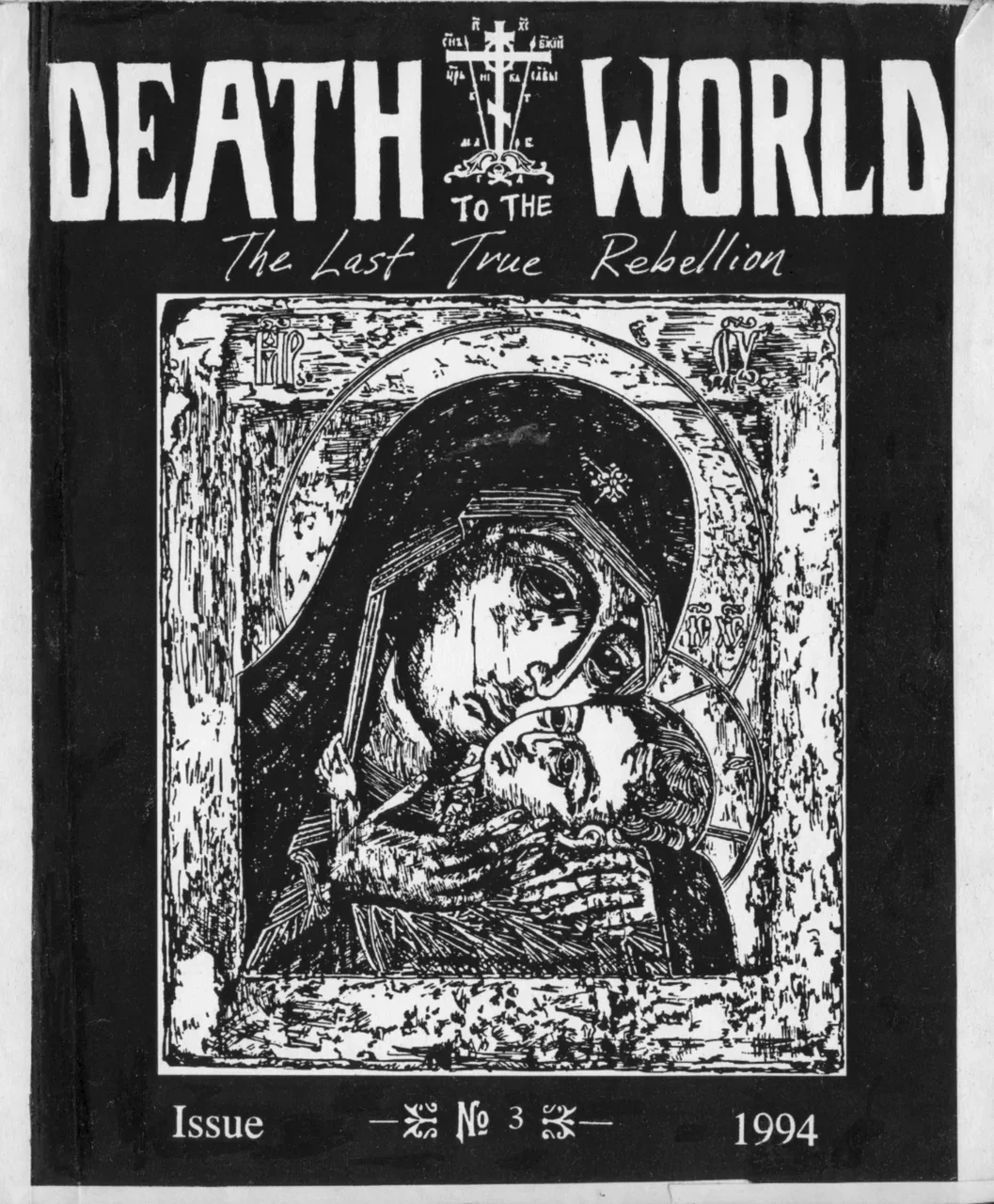

In the early-1990s, no one anticipated that a member of Sleep, the band from San Jose that invented the genre of stoner metal, would become one of the most prominent evangelists for Orthodoxy in the US. As of 1991, Sleep’s debut record had just been released, and it was quickly gaining a huge fanbase. But as his bandmates went on tour, Justin Marler, the guitarist, was already moving in a different direction. He started spending time at the St. Herman of Alaska monastery, where Rev. Seraphim Rose had lived until his death a decade earlier. And in 1994, Marler would launch the publication Death to the World, which would soon galvanize what people still call the “punk-to-monk” phenomenon.

If this were an isolated instance, it would be interesting but not necessarily indicative of any broader trends. However, the connections between punk/metal culture and US Orthodoxy increasingly run deep. There are numerous websites—13th Vigil, Punks and Monks bookstore, and Orthodox Outcast, to name just a few—that directly build on the groundwork laid by Death to the World and its bridges between music and spiritual countercultures. These sites, and the broader movement they represent, channel the rebellious energy of punk into another kind of rebellion against the world, this time spiritual—“the last true rebellion,” as Death to the World puts it.

In thinking about this issue’s theme of “growth,” as it relates to conversion to Eastern Orthodoxy in the United States, my recent research into the intersections of punk rock/heavy metal cultures and Eastern Orthodoxy has helped me discover some patterns and overlaps that are common in contemporary conversion narratives. My recent book, Death to the World and Apocalyptic Theological Aesthetics, examines the story of Death to the World, from its founding as a zine, to its growth into a broader movement, and most recently, its revival as a magazine, merchandise outlet, and influential vanguard for the “punks to monks” aesthetic in Orthodoxy.

In this article, I would like to reflect more broadly on the question of how formation in punk rock and metal cultures sets the aesthetic, sociological, and even theological stages for acclimation to Orthodoxy. My goal is to suggest some reasons why punk/metal subcultures have been, collectively, a fertile ground for the growth of Orthodoxy in the US.

We should say first that this is not the first time rock and roll has intersected with a Christian subculture in the US. Evangelicals have long enjoyed a tense but generative relationship with consumer culture broadly, and music culture more specifically. Leah Payne’s recent study, God Gave Rock and Roll to You, covers this history well.

Indeed, when I was writing about Death to the World’s move to produce more Orthodox-themed merchandise with a heavy-metal aesthetic (t-shirts, hoodies, buttons, patches, and the like), one of my editors asked if I thought Death to the World was simply a case of US Orthodoxy onboarding evangelical merchandising culture. It’s a good question. On one hand, it would be implausible to suggest that any form of Christianity in the US fully evades the long shadow of evangelicals’ influence. However, my answer then, and now, is that the “punk-to-Orthodox” dynamic is not simply an Orthodox version of the same phenomenon.

To illustrate why I believe this to be the case, I want to focus on how formative themes in punk rock and metal cultures resonate with, and are in some ways answered by, the forms of Eastern Orthodoxy to which many converts tend to gravitate.

“‘Death to the World’” and

Apocalyptic Theological Aesthetics

by Robert Saler

Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019

The first theme is that of authenticity. Multiple studies of convert self-reports in US Orthodoxy have stressed the role that “originalism”—that is, the notion that Orthodoxy represents the preservation and perseverance of the original church of the Apostles—plays in their decision to become Orthodox. Similarly, within both punk and metal cultures “authenticity” is a dominant and normative standard—not only for the music itself, but for the lifestyle and subculture participation associated with it. Since long before the internet age, debates have raged about certain bands: are they actually living out the ethos of the subculture, or are they “sellouts” or “poseurs”?

In other words, debates over orthodoxy and heresy are not the sole province of religion. As prominent online Eastern Orthodox influencers such as Fr. Turbo Qualls, Fr. John Valadez, Buck Johnson, and Mano Elia (all of whom identify as converts from punk subculture to Orthodoxy, and who credit punk for playing a role in the transition) have stressed, debates over authenticity in punk culture can acclimate people to seek authenticity in religion as well. Punk critiques of the “phoniness” of mainstream culture easily map onto Orthodox convert critiques of the emptiness of, say, “mainstream” churches capitulating to consumer/entertainment culture. The point is that discourses of originalism and those of authenticity (however contested) are a natural sociological and theological pairing in this case.

With the desire for authenticity, of course, comes parallel suspicions of “authority” to the extent that “the system” or “the mainstream” is seen to perpetuate cultures of phoniness, materialism, and existential emptiness. Under the influence of such figures as Fr. Seraphim Rose, many “punk-to-Orthodox” converts pair despair about the “nihilism” of mainstream culture with suspicion of authorities—sometimes even Orthodox church authorities—whom they deem too cozy with the mainstream—and thus inauthentic. This is an ongoing source of tension among many of these converts, but also the source of the energy behind the claim (which forms Death to the World’s tagline) that Orthodoxy represents “the last true rebellion.”

There is also overlap between metal subcultures and the Orthodox faith. They both put emphasis on the supernatural and otherworldly, as compared to the more immanent or “realistic.” Let me share an illustration from my own life. During the several-year period in which I was discerning my own reception into Orthodoxy, I would sometimes attend my mainline Protestant church’s services at 8:30 a.m. on Sundays, then attend Divine Liturgy at a nearby Orthodox parish at 10 a.m. On one Sunday when I did this, the night before I had attended a death-metal show at a local bar. At that gig, the headlining band performed a track whose title (and shouted chorus) was “Satan is real!” The next morning, I was struck by the fact that this sentiment—that is, the reality of the demonic, and of the spiritual realm more broadly—was present in the Divine Liturgy as well (albeit to a very different end!)

Meanwhile, it would have been completely out of place in my mainline Protestant church. In that way, death metal was more like Orthodoxy (and less like the “disenchanted” secular order) than either was like this Protestant church. From that perspective, it makes sense that people deeply formed in the supernaturalist aesthetics of metal culture (as well as adjacent cultures such as role-play, Dungeons and Dragons, etc.) might be primed to encounter the more supernatural elements of Orthodoxy with recognition and resonance.

This is not meant as an uncritical celebration of the punk-to-monk (or metalhead-to-monk) pipeline. These trends also raise concerns of their own. For instance, it’s not hard to see how the distrust of authority and “the system” that pervades punk subculture can easily morph into suspicion of other cultural authorities—for instance, medical experts who advised masking and vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic (as well as the Orthodox bishops who took those experts seriously). It can feed into a broader problem with conspiracy theorizing that already exists in American Orthodoxy (as I and other scholars have documented). This conspiratorial bent has also, as scholars have shown, complexified the US Orthodox church’s responses to claims made by Russia against Ukraine, the Israel/Palestine conflict, and so on. Put simply, “fight the system” energy tends to be unpredictable as to which systems it targets.

Likewise, too much focus on the “supernatural” (particularly when paired with skepticism towards this-worldly concerns around the poor and marginalized) can be detrimental to the church’s social witness on behalf of justice. The impact of converts upon the culture war is a story yet unfolding, and the dynamics surrounding Death to the World are a part of that. For priests and others who oversee catechesis, these are matters for serious reflection.

That said, we do not want to dampen the work of the Spirit. Indeed, the affinities between punk/metal subcultures and Orthodoxy show us that continuing growth in US Orthodoxy, in many cases, represents less a repudiation of US culture and more a transmogrification of its energies. Some of the trends we see in punk and metal cultures—young people searching for authenticity, rebelling against unjust systems, and expanding their imagination for transcendence, against the metaphysically flattening structures of modernity—can have a galvanizing effect on the Church, when these newcomers are properly catechized.

The full scope of this impact remains to be seen, and we haven’t entirely figured out what it looks like for this energy to be channeled properly. But we should remember that the church has a long history of adapting cultural disenchantment into vital spirituality, and thus we can be both calm and open to surprise as to what God will do with punks, monks, and all of us in between.

Robert Saler is Associate Professor of Theology and Culture, as well as Associate Dean for Evaluation, at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis. He is the author or editor of six books, most recently “Death to the World” and Apocalyptic Theological Aesthetics (Bloomsbury, 2024).