That “Motley Throng”: Growing the Church, Riffraff and All

JUSTIN JACKSON

In Exodus 12:37-38, as the Israelites prepare to follow their God, to throw off their bondage and to worship the God of Israel as Moses has implored, we are told that “… the sons of Israel marched from Ramesses to Sokchotha; the men were about six hundred thousand foot soldiers, apart from the chattels. And a great mixed crowd went up with them, and sheep and oxen, even a great many animals.”

I am not here to question the accuracy of this prodigious number—600,000 foot-soldiers (which, including women and children, would bring us to around two million sojourners); after all, Exodus 1 and 2 explain the miraculous fecundity of the Israelites as they suffer in their bondage (indeed, even becoming more fruitful as they suffer under their hardships!). Rather, in light of our theme, “growth,” I’m interested in what Exodus 12:38 describes as the ‘erev rav (or ‘erevrav; epimiktos polys, in the Septuagint), that “mixed crowd/mixed multitude” who sojourn with the Israelites. The rabbis were interested in who made up that “mixed multitude” and about what imprint those members made on the exodus. Opinions, of course, varied. However, the vast majority of exegetes agreed that this group was made up of non-Israelites—and, more to the point, that they were those witnesses who wished to follow God more than to follow Pharaoh. These witnesses to the great plagues decided to follow the very God who sent these plagues rather than to obey Pharaoh, their god, any longer.

This brief passage always takes my students aback a little, and this surprises me because 1) I teach at a Christian college, and 2) by this time, they’ve already had six weeks of my showing them the ways in which “exile and return” is a paradigmatic structure within Old Testament narrative; i.e., it offers us constant and repeated penitential narratives and models for our turning (back) to God. When we read with this paradigm in mind, which should be a default mode for Orthodox Christians, the Old Testament literarily (and thus quite literally) attempts to demonstrate that God desires not the death of sinners but that they should turn and live (Ez. 18:23).

Perhaps the reason for my students’ reluctance to think about non-Israelites as would-be Israelites is that they’ve previously been taught about certain supposedly (and actual) exclusivist claims made by the Hebrew Bible, claims misunderstood by ancient readers and yet illumined and corrected by the New Testament. But this still strikes me as odd, because by this time we’ve also read the Book of Jonah—wherein the future persecutors of the Israelites, the Assyrians, have been spared by God even before they’ve persecuted the Israelites. Still, God shows all of them great mercy, even if only temporarily. And the Ninevites’ repentance is even highlighted and praised by St. Matthew as he recalls this sign of Jonah (12:38-41). In a nutshell, my students will accept and even be delighted by the repentance of the Ninevites, the very people set to besiege the Israelites within 50 years of when the Book of Jonah is set, yet they are taken aback that such foreign entities—this ‘erev rav—would be spared, or even that such riffraff would be allowed on the Exodus with faithful Israelites.

This notion of the outsider as a model for Israel (and as a model for Scripture’s readers) should hardly take any Orthodox Christian by surprise: we read St. Andrew’s Great Canon twice during Lent (just in case it doesn’t stick the first time—or, for some of us, the 61st time!). But if we simply read the genealogies of the New Testament during the Nativity fast, for example, then we can hardly be scandalized. Indeed, Christianity seems to be, by God’s own decree, a group of outsiders, riffraff even. It’s a scandalous list but hardly surprising, and I’m not referring only to Holy Prophet-King David. Repeatedly, depictions of the ancient Church in the Old Testament demonstrate the ways in which the outsider is brought into Israel—and it’s often simply through obedience (even if monolatry at times), by faith, doing those things commanded by God.

I’ve already mentioned the Ninevites, who took on Israelite penitential practices without even knowing what they’re doing. But to this we can add Ruth. She’s the Moabite, which our narrator repeatedly points out, but Naomi and Boaz see her only as an insider, as family, because of her actions and because of her fidelity to Naomi (and thus to Naomi’s God). We can add Hagar, Sarah’s Egyptian slave girl. When pregnant with Ishmael, she is chased away by Sarai where the angel confronts her in the wilderness, asking her where she is going, and she is told that God has heard her suffering; so “now go suffer” (Gen. 16:9-12). There are few formulae in the Old Testament that map out the history of Israel (or the Church) better than this: God has heard your suffering; now go suffer. Perhaps more appropriate here, we can look to Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law and a priest of Midian. After the exodus, when the Israelites have been freed by dint of God’s hand (manifested through Moses’ hand), and right in the midst of their murmurings and disobedience, Jethro shows up again. He’s a foreign priest but one who has heard of the glories of God. In contrast to the Israelites, he’s delighted by the miracles and the protection of this new God and simply asks Moses, “Where do I sign up?” (my own rough translation of the Hebrew).

The growth of Israel (and thus the ancient Church) is an odd thing to behold. If we follow the pattern, there always seems to be a catastrophe or disaster leaving us with a remnant of the faithful, then adding others to that remnant, then maybe another loss, another remnant, another loss, and so on. It seems that our best models for behavior come from the outside and that Scripture works hard to make us conscious of this phenomenon. While we keep looking for purity from within Israel, the sacred text may be asking us to look to the earnest desire for God from outsiders who yet still serve other gods and thus are left with a sense of insatiable wanting. If the messianic promise is a universal harmony (howsoever imagined), then it makes sense that the marginalized become central to that narrative—that outsiders are brought to the messianic meal, as it were. The margins will help to build the center (taking our cue from the stone which has been rejected).

Every American Orthodox Christian ought to understand this basic, evident principle: at the birth of Orthodoxy in America were the marginalized, the immigrant (my own grandparents), those bringing this foreign Christianity to these shores. But also, after time, the immigrant Orthodox Church needed to understand fully what it was bringing to the Americas: the Church. Do we wish it to grow and to witness Christ’s love of this people? If so, then that’s going to take “outsiders” (except “outsiders” here means western converts and not immigrants). So whereas Orthodoxy was once itself a stranger in a strange land in America (as Orthodox immigrants), it has now found itself a stranger (American Orthodox Christians converts) in a strange land (European, Eastern European, and Near Eastern Orthodoxy). I find it all sublimely biblical, and even prophetic.

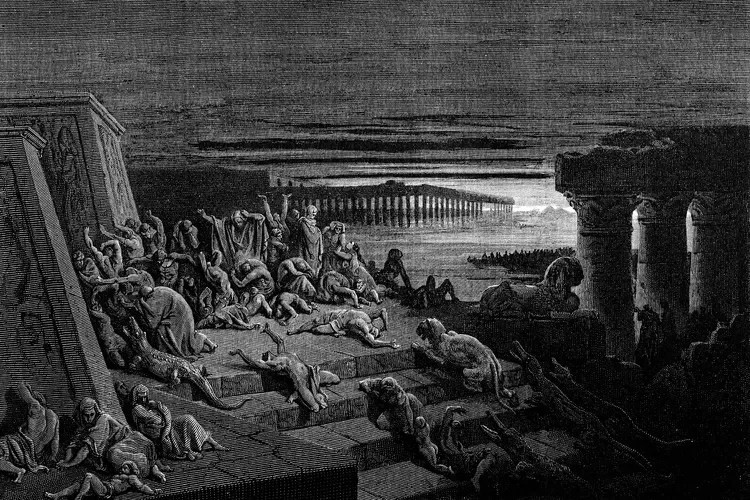

So now let us return to the ‘erev rav, the freeing of Israel from the bondage of Pharaoh and death, and let’s think about life in the Church, the Body of Christ. If this ‘erev rav are outsiders, then one has to ask how did these outsiders come to worship this foreign God? And what an odd thing to imagine that a God who brings plagues upon a people would also be a God who wishes to be in communion with those same people. But I believe that’s where we are in this story. Every plague unleashed by God on Egypt is a call for them to turn to the God of Israel, to Christ. The narrative logic of the plagues demonstrates that two things are at play in God’s warning (yes, warning) to the Egyptians and to the Israelites: that this God can bring death, and that this God can hedge in any of those who obey.

The Nile, turned to blood and stinking like death, is the first indication that this is a God who controls the Nile and thus the Egyptians’ lifeblood (and thus the gods associated with the Nile). That stench of death is a prophetic warning of what is to come. The plague of frogs will do the same thing: they stink like death. But they invade and demonstrate that this God can get close to us with this death and that there’s nothing one can do about it. The plague of lice simply magnifies the proximity of God to our own being. If death looks like lice, then we are in trouble. Even the Egyptian magicians can do nothing against the lice.

God then begins to demonstrate that while He can utilize these vehicles that remind us of death and can also show that He can bring it close to our very persons, He can also distinguish and protect those who obey His commands. So when the Israelites’ land and livestock are spared from destruction (the fourth and fifth plagues), we witness that obedience does not lead to death; indeed, obedience leads to a preservation of life. And it seems to be an easy obedience, one that serves the livelihood of the Israelites: obey God and avoid destruction (this may be the eschatological teaching par excellence).

Here, we begin to witness a much more focused prophetic warning: this god is a God who can control death (and is not controlled by it) and who can bring it in closer proximity to us (indeed on our very selves, like lice). But now in the seventh plague we see an important shift. God has warned of the next plague and says that whoever obeys and brings in their livestock and servants, then that livestock and those servants shall be spared: “Thus he who feared the word of the Lord among Pharaoh’s servants gathered his cattle into his houses” (9:20). It’s a brief, remarkable line, easily overlooked, but it certainly begins to give us a sense of who are the ‘erev rav: these are the outsiders who can read prophetically, who understand that God can hedge in those who desire His protection, and so they do the unthinkable: they obey this new God whom they do not know. And their livelihood is spared. The text has moved us from what at first appears to be injustice—“I will harden Pharaoh’s heart” (how can Pharaoh be punished for the very thing God did to him?)—to God saving those Egyptians who obey Moses’ prophetic words. In short, those who listen to and obey God become Israel.

I don’t believe this reading becomes merely an example of a hermeneutic of an extreme misericordia (though I could be accused of far worse). I’d simply point out that Scripture makes it plain that God’s deliverance of the Egyptians was not simply to show His power or sovereignty as a sort of reason for all of His actions; rather, His warnings and actions (the plagues) were always only a means of moral instruction (for the Israelites and Egyptians alike): obey and you shall live.

When the Israelite midwives refuse to do Pharaoh’s bidding and murder the Israelite children, we are told that they “saved the male children alive” (1:17). They disobeyed one god (Pharaoh) only to serve their own, whether they knew it or not, even though their God seemingly had abandoned them. When Pharaoh’s own daughter disobeys her father (and her god) and saves the future prophet of Israel, Moses, she too obeys Israel’s God; sometimes a simple act of moral rebellion can be a great act of faith. Indeed, after Pharaoh’s daughter protects Moses, we are told that “God heard their groaning, and God remembered His covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Then God looked upon the children of Israel and was made known to them” (2:24-45). The only question that remains is: Who are these children of Israel? The answer is, I think Scripture makes clear, those who follow these commandments of this foreign God (who Himself is an outsider in Egypt—and even to His own people!).

When the ninth plague arrives, the most overlooked plague as far as I can tell (probably because it entails no destruction), it bears direct witness to all the other plagues and to the coming of the tenth. We are told that all the land experienced darkness, “a darkness that may be felt” (10:21). Because God has been warning them about death and His ability to bring it upon their very existence, I believe this is a prophetic warning about the death that is coming, that this darkness is quite literally God bringing Sheol (Hades) to Egypt. This is a darkness that hangs on them like lice for three days. While the Egyptians wander in darkness (Sheol), the Israelites have the light (life, Christ Himself).

The Egyptians who have witnessed this God’s protection over the Israelites and even themselves now must “feel that death,” being cut off from all others in darkness, separated, isolated, while the Israelites can feel the light, the kavod (the Glory) of God, and thus see the face of their neighbor. God can obviously save the Israelites from this death, so when the threat of the tenth plague comes (the death of the firstborn) and when the Israelites are told how to avoid said death, it would make perfect sense that the ‘erev rav, these outsiders, this riffraff, would again follow suit and listen to this new God, look to the Israelites as a model, and even butcher and eat prohibited animals (a lamb, for example—holy in Egypt). “Do this, and you shall live” becomes an imperative for the Israelites and all these other nations—Egyptians and whatever other foreign people may be there. Do you desire life and to obey God? Then there will be great suffering, but also true freedom (living a life in virtue) and true life, eternal life.

And that’s what these outsiders have discovered and chosen: a God who gives life, who commands obedience, who can defeat these other gods, and who protects His people from death (and offers eternal life). When God reveals His name to Moses a second time on Sinai, “The Lord God, compassionate, merciful, longsuffering, abounding in mercy and true” (34:6), we start to get a sense of why this is His name, and why it is His name for the Church: because who can survive without these divine attributes? If God desires not the death of a sinner but that he turn and live, then we need His compassion and long-suffering. This is a God of the ‘erevrav, we riffraff who do little right but who have seen the light and desire it, who have seen God, tasted Him, and desire more—even when we worship that golden calf.

The ‘erevrav, I am convinced, are the cornerstone of the Church. The ‘erevrav may be outsiders, riffraff even, but they are not stupid (though some of us are). They see the source of life and follow Him even if they do not fully understand. But I also take this as a definition of life in the Church, which does not mean to give up one’s rational faculty, but rather to follow it, to read the writing on the wall, as it were, and to follow this God even when we don’t fully understand. This is no blind obedience but a way of reading prophetically, to see all of our various entanglements and yet to be able to read in advance the end of those entanglements—as either walkers in darkness or in light.

I will end with one final observation because my exegesis here, I admit, is rather loose and is based more on the Hebrew than the Greek (probably so), which brings me to Pharaoh’s daughter. She has a name; indeed, she is included in the genealogy of Israel in 1 Chron 4:18. This daughter of Pharaoh, Bat Paro (literally daughter of Pharaoh), Bithia, was one of the ‘erevrav—certainly one of the first in her disobedience of her father and god, Pharaoh. Rather, she let this this riffraff, this Moses, live, and she feared God. This is why in the rabbinic tradition she is known as Bat Yah, daughter of God. I think it fair to say that when she disobeys her own father, she is already clearly one of the ‘erevrav to him (much like the Israelite midwives), but in this way she became a child of God.

When we think about the growth of the Church—how to grow it, where to grow it—and shudder a bit because of the violence, injustice, perversity, and utter banality of so much of what we must face spiritually day-to-day in this world, let us look back on this riffraff and consider their own sacrifice: they followed a God they did not know and for only one reason—to live. They turned from their own gods, and from the shame and punishments they’d find therein in that disobedience, and they followed an invisible God. Or, even better, they followed the hand of this God through the hand of Moses, an old man who couldn’t speak well, who wasn’t even sure if he liked this people, and who kept bringing them more suffering (but also life).

The life of the Church is a life of repentance, a turning to God, indeed to life itself, and no one tastes this desire for life quite like the riffraff, because we know the emptiness of all of our vain pursuits. Like the ‘erevrav, we may not know why we are doing what we’re being asked to do, but we know our life depends on it, and we know of God’s mercy, His compassion, and His longsuffering. There is no other God for the riffraff than Christ our God, longsuffering, who takes the weakest and builds His Church upon them. It is upon a God of mercy and compassion and upon a repentant people that the Church shall grow.

Fr. Deacon Justin Jackson serves at Holy Ascension Orthodox Church in Albion, MI. He is professor and chair of English at Hillsdale College. He runs a substack—How Do You Read It?—wherein he goes through various literary readings of the Hebrew Bible and other texts. https://bibleandliterature.substack.com/