“A Baptism of Sound”:

A conversation with Mother Katherine Weston on composing

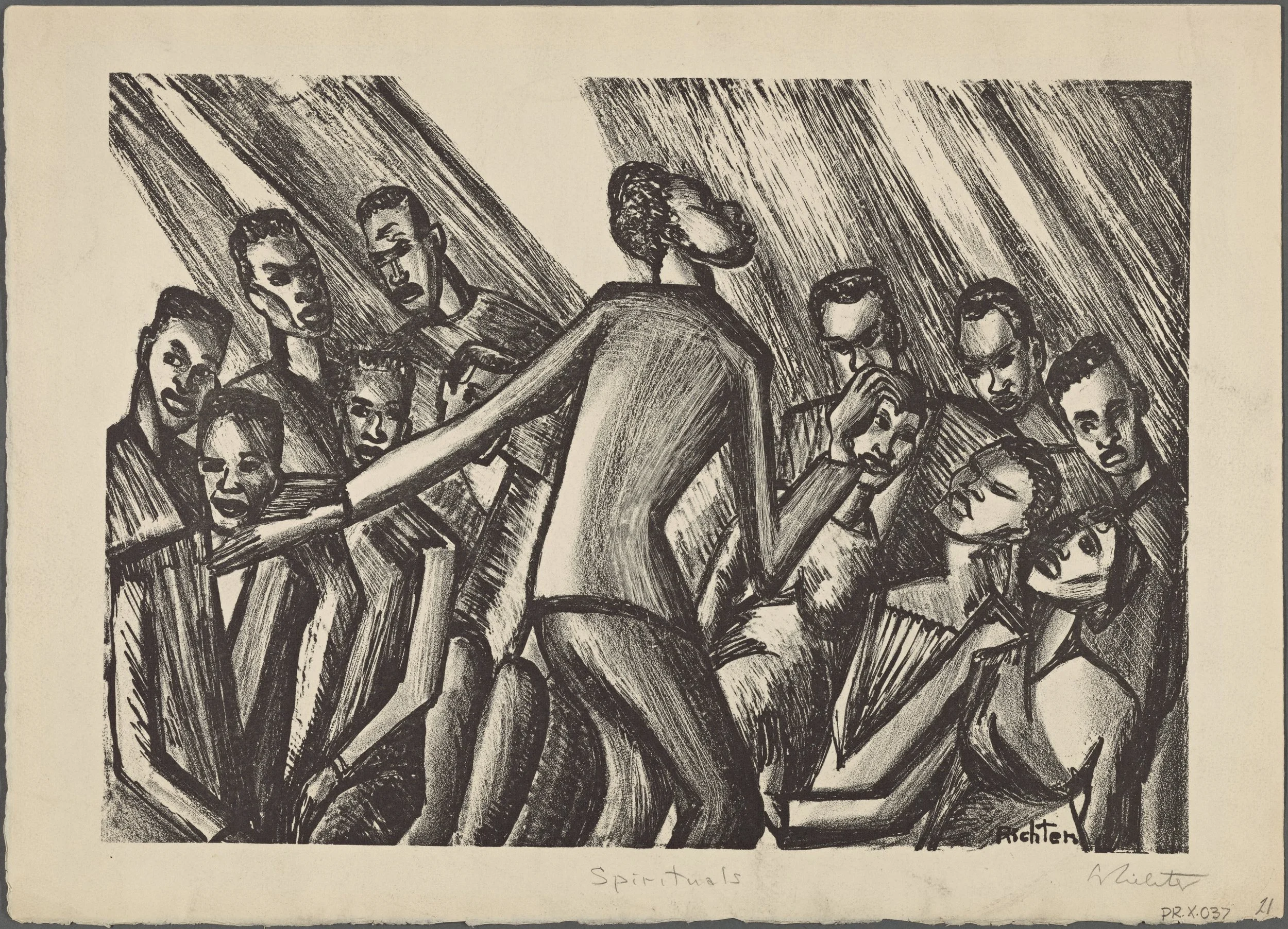

Over the past decade, there has been a swell of new Orthodox liturgical music by American composers. Benedict Sheehan, a three-time Grammy nominee, has likely been the most visible example of this trend; but there are others, composing in different styles, whose settings of Orthodox hymns are now being used in parishes throughout the US, including Kurt Sander, Samuel Herron, John Michael Boyer, and nazo zakkak. But no one is doing work more groundbreaking than Mother Katherine Weston, the abbess of St. Xenia Methochion Monastery in Indianapolis, whose compositions draw heavily on African American spirituals. Her “Jubilee Liturgy,” a complete setting of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, premiered at the 2023 conference of the Fellowship of St. Moses the Black (of which she is the president).

In an interview conducted over email, I spoke with Mother Katherine about the underlying connections between Orthodoxy and the Black church tradition, her own composition process, and what the flourishing of new liturgical music tells us about the state of American Orthodoxy.

- Nick Tabor

NT: It’s my understanding that before you joined the Orthodox Church, you were Episcopalian—and you were drawn to Orthodoxy, in part, by the Church’s music. Could you say more about that? Did you have a musical background? What about the music was compelling for you?

Mother Katherine: I was drawn by the beauty—both the iconography and the music, not yet having exposure to Orthodox church architecture. Of course you can find beauty in the Episcopal Church as well, but by the time I fell in love with Orthodox art forms, I had long migrated away from the church I was born into. We’re talking about the late 1980s. I was on the staff of the Raphael House Family Shelter in San Francisco, and the staff members were exploring Orthodoxy together. Our choir director assembled a large group of singers to learn Rachmaninoff’s All-night Vigil. The many rehearsals, the performance in a church, and a final performance in a redwood forest: Believe it or not, all this allowed the music to steep through my soul. It was a big part of my preparation for baptism. In fact, if baptizo (βαπτίζω) literally means to immerse, then singing Rachmaninoff was a “baptism” of sound. Being in a large choir, breathing and singing as one—this could introduce the feeling of being part of a body, the body of Christ, not just an isolated individual. You don’t get this same experience in a Protestant service, singing short, individual hymns.

Did I have a musical background? I came from a music-loving family. Everyone played some piano, everyone sang. I’ve sung in choirs or at the kliros my entire life since grade school. I flunked out of violin and piano lessons, though, but I picked up guitar at age 11. Over the years, I have played for both pleasure and informal performances. Providentially, I learned enough music theory in childhood to score out the little songs I wrote—you could say that music notation became a hobby. And that was very important later on.

People often seem more surprised when they hear about Black Orthodox converts than white ones. But Fr. Paul Abernathy says elsewhere in this issue that he’s had Black visitors to his parish in Pittsburgh who immediately feel at home with the Orthodox Liturgy, in part because they feel like there’s a connection between Orthodox music and African American spirituals. Was that a factor for you, and have you encountered it with others? If you do see a connection there, I’d love for you to say more about it.

There is an important connection between the spirit of Orthodox music and African American spirituals, but I was not aware of this initially. The connection is joyful sorrow—what the Greeks call harmolypi (χαρμολύπη). This has to do with really and truly having God as our only hope in this world—not our wealth, not our status, not our strength, but God alone. And it has to do with experiencing God as our joy in the midst of earthly tribulations. My enslaved ancestors—that is, the enslaved Christians in America—had this in common with the early martyrs and persecuted Christians. This spirit is embedded in the spirituals and in our Orthodox music, even though we moderns have to struggle not to trust in ourselves.

I became aware of the connection between the ethos of Orthodox music and the spirituals through the Fellowship of St. Moses the Black (FSMB), of which I am a founding member and the current President. In our earliest conferences, in the 1990s, we heard a talk by Fr. Damascene (Christensen) on that topic. Fr. Moses,3 of blessed memory, spoke about Gospel music as well. Fr. Damascene and Dr. Al Raboteau, of blessed memory, both spoke of the African American slave martyrs and confessors. These themes have been curated and built upon in our two volumes, Foundations: 1994–1997 and Jubilation: Cultures of Sacred Music. Fr. Alexii Altschul, our Spiritual Advisor, also speaks extensively on this topic in Wade in the River: The Story of the African Christian Faith. Without this groundwork, I would have had no reason to compose any liturgical settings.

When did you begin writing your own arrangements of liturgical music, and how did that project come about? Did it have anything to do with your work with the Fellowship of St. Moses the Black?

Yes, my composing was always bound up with the Fellowship’s work. At our 2005 conference in Denver, Fr. Martin Ritsi of the Orthodox Christian Mission Center was the guest speaker. During the final presentation, after sharing with us about the mission work in Africa, he turned to us and asked, “Why don’t you use the spirituals as inspiration for liturgical music as part of your own evangelical outreach?” Oh my goodness, the gathering exploded with excitement. Clusters of people were sharing their inspirations for what could work. We were still sharing on the ride to the airport afterwards.

I had an idea too—but I had the advantage of my experience in music notation. So I went home and scored out my Anaphora based on “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?” That first draft needed more development, but parts of it are still embedded in how we sing it today. In this setting, the Anaphora answers the question “Were you there?” with “I am there as a witness to Christ’s Passion and Resurrection in the Divine Liturgy.” And the idea of having the words of the spiritual in dialogue with the liturgical moment continues to be part of my process today.

It might say something about the development of Orthodoxy in the U.S. that we’re at a stage where we’re adapting our liturgical practices to the local cultures. Do you have any thoughts about that?

Yes, there have been conversations in seminaries and among American Orthodox church musicians for decades now about finding an authentic American expression of Orthodox music. Certainly at St. Vladimir’s and St. Tikhon’s. They primarily see two authentic sources for that inspiration—sacred harp and spirituals. You might think of sacred harp as Appalachian music—but some black churches have used this tradition as well. There are several composers incorporating Americana elements in their works. Benedict Sheehan, Archpriest John Finley, Monk Martin (Gardner), Dr. Vladimir Morosan, Dr. Shawn “Thunder” Wallace, and nazo zakkak are all ones whose work I am familiar with. There’s a whole chapter in Jubilation devoted to this question. But it’s bidirectional—that is, a parish or organization may commission a piece to reflect local cultures—so it’s not just coming from the musicians.

What does that mean about the stage we’re at? I don’t mean this in a negative way, but the Orthodox Churches in America are no longer just immigrant congregations trying to preserve their own culture. Remember that some of the older parishes were founded by ethnic clubs that valued their faith enough to build their own houses of worship. That’s a beautiful thing. And now the Orthodox Church has taken root in this soil and among this diverse group of people who make up the U.S. So now people are looking for authentic cultural roots here so we can make a cultural offering to Christ from the collective heritage He has given us. “Thine own of thine own.”

What do you hope to achieve by arranging Orthodox hymns in a way that’s inspired by African American spirituals? I’m sure it brings you some amount of creative fulfillment, but does it also have a larger pastoral purpose? Do you see it as a form of missionizing?

I’ve heard composer and conductor Benedict Sheehan say that certain music “sounds like church” to someone or some group. I’ve come to believe that just as we receive an imprint of our native language early in childhood, we can also receive an imprint of worship music. And that’s what “sounds like church” to us throughout our lives. There are different ways in which spirituals can inspire Orthodox liturgical music and I’m not, by far, the only composer inspired this way. But when people hear my Jubilee Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, it does “sound like church” to some people. And this is not necessarily along racial lines. The spirituals have entered the mainstream of American worship music. So white Orthodox converts from the South have really responded to it. One priest said, “It’s like being in church and at home at the same time.” When I heard my Trisagion sung in Liturgy for the first time, I felt like a deep part of my soul was able to be present that had not fully participated before, even though I had worshipped as an Orthodox for over 30 years. Likewise, there are some black people who really resonate with it, but some who criticize me. They might have been brought up on the Gospel style or call-and-response, and that’s what “sounds like church” to them. I respect that, and I hope to be an inspiration to a new generation of composers, but I can only create in a way that is authentic to my own musical background and experience.

On one hand, we’re a church that reveres its traditions and is slow to make changes. But on the other, there’s a case to be made that as the demographics of American Orthodox parishes change—so that we have fewer people who were raised in Orthodox ethnic cultures, and more converts—it can become inauthentic for us to keep doing everything in a strictly Greek or Slavic fashion. It can become a kind of cosplay. My question is, how do we change our practices while still being faithful to the tradition?

That’s an important question, and I can only answer based on how I approach it. So first of all, I don’t compose in isolation. I consult with Dr. Zhanna Lehmann, who has extensive musical training and experience. She began her musical education at the Kazan State Musical Conservatory in Russia and then earned her doctorate in Choral Conducting at the University of Illinois in 2018. A mutual friend introduced us in 2021 when she was looking for new and interesting liturgical scores for a Nativity concert—and I was looking for a choir to sing my music. (Unlike many composers, I’m not a choir director.) When she heard that someone was writing Orthodox liturgical music based on spirituals, she was very excited because she first encountered and sang African American spirituals in Russia. She told me that Russian people love our spirituals because they have a resonance with certain genres of Russian music, especially religious folk music and “penitential psalms.” I can’t break it down here, but that genre of singing was actively developed for a couple of centuries, through the 1600s. Because of this history, the American spirituals feel familiar to Russians.

Now I’ll go back to your question of how we change our practices while staying true to tradition. Centuries ago, as our faith took root in Slavic countries, there was a natural inculturation of the liturgical chant—it absorbed some of the flavor of the local folk music. This was an organic development seeing that the folk music expressed the identity of the people. Russian composers—Glinka, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov—they all incorporated elements of Russian folk music into their masterworks. So as a composer, I am attempting to walk in their footsteps by taking inspiration from the spirituals—the only music completely original to the U.S.—to touch the souls of African Americans, of Americans, and beyond. Because the spirituals have had an international audience since the post-Civil War period. So in short, we maintain the tradition by changing in an organic, traditional way.

Perhaps you could give us an example, explaining how one of your arrangements came about?

I said something earlier about the beginning of my first liturgical composition, the Anaphora. Now let’s talk about the Trisagion, one of my favorites. In the summer of 2022, Dr. Lehmann said she thought I was ready to complete a setting for the entire Divine Liturgy since I already had so many of the elements written already. It was still necessary to arrange a Trisagion. I generally comb through the spirituals I know, that I have in written collections, and that I can find recordings for. I look for slower melodies, which already eliminates a majority of them. On YouTube I came across the great Marian Anderson singing “You hear the lambs a-cryin’” in her inimitable contralto voice. The music was so simple and deeply stirring. The lyrics are a dialogue between our Lord and Peter based on John 21:15–17. “You hear the lambs a-cryin’, O shepherd, feed-a my sheep.” In the Trisagion, the rational sheep of Christ no longer cry out in inchoate moans, but they cry, “Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us!” In the Divine Liturgy, they are fed on the word and on the Holy Eucharist.

There seems to be a trend in Orthodox composition towards becoming more ethereal, more transcendent. But my compositions reflect His Incarnation and His immanence. In my notes to the conductor for the Trisagion, I write, “We are carrying baskets, heavy with all the concerns for which we plead God’s mercy—for ourselves, our loved ones, the sick, the suffering, the imprisoned. Those in a place of war …. We offer all this to the Lord in a hymn rich with earthy harmonies and heartfelt pain. And the Lord hears us.” The Fellowship has a documentary of the premiere of the Jubilee Liturgy—Houston, Texas, 2023 on YouTube. We sang it again last year in Indianapolis and I’m still working on making the audio recording available.

What has been the response to the music you’ve published? Is it being used in parishes? Have you encountered any skepticism, and if so, how have you responded?

The initial response shocked me in a good way. I had been working in my own bubble, unaware of the conversations happening in Orthodox seminaries and among Church musicians. What we talked about earlier—looking for authentic American inspirations. And then as I was editing Jubilation: Cultures of Sacred Music, I needed to connect with and interview various American Orthodox musicians and composers. That’s when I learned that they had been waiting for someone like me. It was something, I imagine, like the surprise of an infant emerging from the internal solitude of its mother to the arms of a loving family. Dr. Lehmann, whom I mentioned before, premiered several of my hymns with her Illinois Orthodox Choir—in 2021, the “Our Father,” “It is Right, Indeed,” the Cherubic Hymn. In 2022, the Polyeleos and a Paschal Troparion—and they have continued.

Dr. Peter Bouteneff has been a supporter from the beginning. He invited me to participate in a couple of podcasts. The first, a panel discussion in collaboration with Cappella Romana, was in May of 2021. The second was a conversation between just the two of us for his Luminous podcast. St. Vladimir’s Seminary invited me to present at its Summer Sacred Music Institute in 2023. There I was introduced to the conductors who rehearsed four of my pieces with the group of over 30 singers. And then to my surprise, they incorporated them into the Hierarchical Divine Liturgy which culminated the week. Juliana Woodill was one of them—she has since performed two of my pieces with her Archdiocesan Choir of Washington, D.C. Dr. Alexander Lingas, musical director of Cappella Romana, sang in the Houston premiere of the Jubilee Liturgy in view of performing five selections in concert in February of 2024. This concert, “How Sweet the Sound,” was a collaboration between Cappella Romana and the Gospel group, Kingdom Sound, directed by Derrick McDuffey. Each of my selections was prefaced by a rendition of the spiritual which inspired it. It was a great vision and a great execution—we’re hoping to do something more in the future. Dr. Lehmann has also introduced some of our pieces at the Sacred Music Institutes of the Antiochian Archdiocese. If I’ve forgotten a musician, I hope they’ll both forgive me and jog my memory. It’s no reflection on them.

I have my critics, too, as I said earlier. Those who are comfortable bringing their thoughts to me are my fellow Black people. Some have said that my compositions are little more than Russian-style Church music with some syncopation and some call-and-response added. But any Black person hearing it for the first time comes as a guardian of their own worship-music traditions. They come with strong hopes and fears. You know the feeling when your favorite novel is made into a movie—are they going to get it right? Will the characters look and sound as you envisioned them in your own mind? They want to know, “will it sound like church” to them.

In all fairness, I do have deep Slavic musical roots because that’s what I’ve chanted and sung as a monastic for over thirty years. And the Slavic four-part harmony—which is not a Slavic invention but an integral part of Western music—is well-suited for interpreting the spirituals. Here’s why—shortly after emancipation, Jubilee Choirs were formed at black colleges and in the communities as well. They brought the spirituals to the stage for the first time, and they sang in four-part choral groups. The best known, which are still singing to this day, are the Fisk Jubilee Singers. So stylistically speaking, finding inspiration in the spirituals for four-part liturgical compositions just makes sense. But in Gospel singing you have a soloist and backup choir. The soloists make use of a lot of improvisational melisma, just as you find in some Byzantine chant. Perhaps another composer will explore the intersection of those two genres.

But on the ground is where it really counts—are my liturgical settings being sung in parishes? Certainly, but I don’t know to what extent. It’s apparently quite rare to hear a Divine Liturgy sung “from Amen to Amen” all from the same setting or composer. These Liturgies become celebratory occasions given that a choir must be assembled to rehearse an hour and a half of new music—that’s quite a commitment and quite a feat! Most often, parish conductors wanting to introduce a little variety look for litanies, a Trisagion, a Cherubic Hymn, and hymns to sing during the communion of the clergy and the faithful. Musicians go home from Church conferences with new scores and introduce them to their home parish. Some of my scores are downloadable from the Fellowship website. So bit by bit, these little compositions take wing and occasionally someone will tell me that they’re singing something at their parish. My dream is always this: that somewhere an African American family will visit an Orthodox parish for the first time and hear one of these pieces sung. And they’ll recognize that the Orthodox Church indeed has its tent flaps open to them.