Stillness Amid Chaos: Reflections of an Orthodox Christian Lawyer on the Jesus Prayer

CHARLES E.A. LINCOLN, IV

When readers pick up the lesser-known novels of J.D. Salinger—going beyond The Catcher in the Rye, his quintessential portrait of 1950s Americana, which remains a staple of high-school curricula—they’re usually not expecting an introduction to the deeply esoteric traditions of Orthodox Christianity. And yet, there he is, in Franny and Zooey, unpacking the Jesus Prayer—which had been whispered in quiet monasteries on Mount Athos for centuries before it was shouted into the chaos of the Glass family’s living room in mid-20th-century New York.

It’s a striking juxtaposition, but Salinger makes it work. In fact, he uses it to crack open something universal: the deep hunger for authenticity, meaning, and connection to the divine in a world that often feels overwhelmingly false.

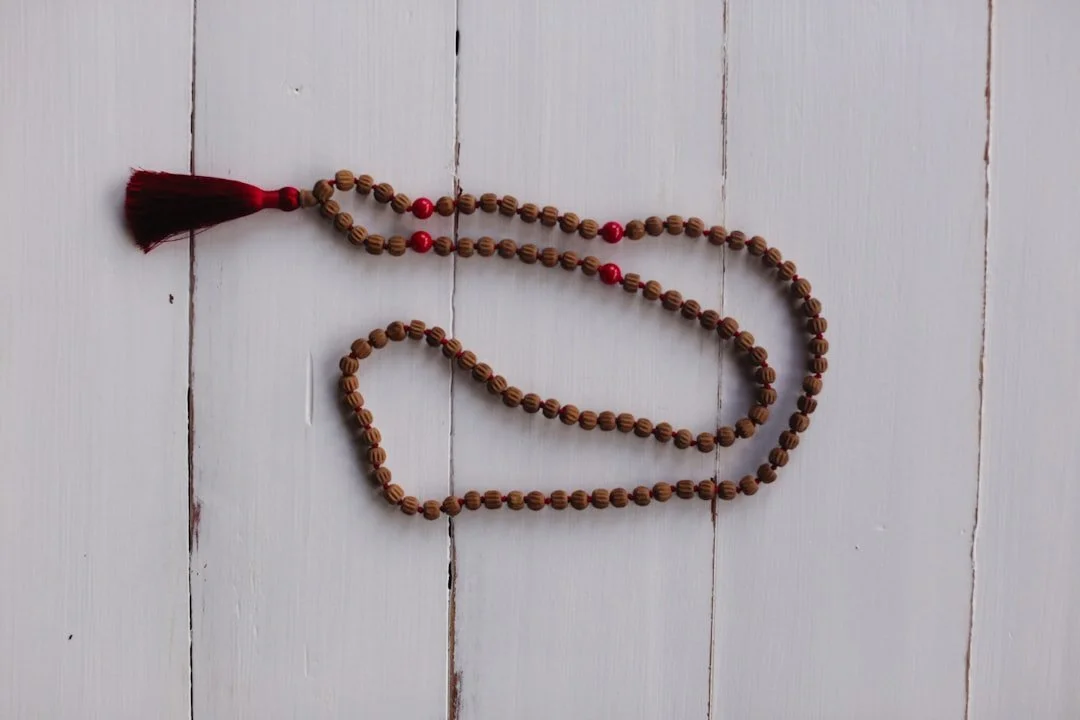

Franny and Zooey consists of two stories about the youngest siblings in the Glass family, who are the focus of much of Salinger's fiction. The brother, Zooey, and sister, Franny, are brilliant and more than a bit neurotic. Franny has a nervous breakdown, and she takes solace in a 19th-century Russian spiritual classic well known in Orthodox circles: The Way of a Pilgrim. Franny herself clings to like a life raft in a sea of modern disillusionment. The pilgrim, like Franny, seeks meaning in a fragmented world, finding solace in the ceaseless repetition of “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

As a Greek Orthodox Christian lawyer, I often think about how this same juxtaposition plays out in my own life. In courtrooms and conference rooms, and while writing memos, the Jesus Prayer feels almost out of place—an ancient phrase carried into a world of modernity and legal jargon. But, as in Salinger’s writing, that dissonance is precisely the point. It’s not about fitting the prayer into the world; it’s about letting the prayer reframe how I see the world. Like Franny, I often find myself repeating “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner” in moments when everything feels too loud, too fast, too shallow.

And like Zooey, I’ve had to confront the fact that the prayer isn’t just a way to “escape” the phoniness around me. It’s a way to confront it—to see Christ in the people I’d rather ignore, to engage with the tasks I’d rather avoid, and to embrace the flaws in myself that I’d rather deny.

It’s surprising that Salinger—so rooted in American individualism—found his way to a prayer that’s all about surrendering the self. But maybe that’s the genius of Franny and Zooey. It reminds us that the hunger for something greater transcends time, culture, and even the conventions of mid-century American literature.

All of us—or so it seems to me—experience an existential crisis at one or more points in our lives. Indeed, it can even be a general condition we live in for long stretches. It may affect our religious belief, or it may not. In my own life, I’ve seen how some people lose their faith during such times, overwhelmed by the weight of uncertainty. Their pain resonates with me, and I always hope they find a path to healing and peace.

For my part, the Jesus Prayer has helped me stay more focused and has given me hope for a better future. Like the pilgrim wandering through 19th-century Russia, or Franny sitting in that living room, I have found that this ancient prayer has a way of making even the most chaotic modern life feel anchored. And that chaos is not always existential; it is often the relentless anxiety of work itself. The stress of being a lawyer affects me on a physiological level, and I’ve spoken with others who feel the same. In those moments, I have found solace in silently repeating the Jesus Prayer to myself: 'Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.'