“Were you there?”

The Evangelical Witness of Sacramental Encounter Among African Americans in the Orthodox Church

REV. PAUL ABERNATHY

She stood in tears at the back of the church. They seemed to flow ceaselessly, while the faithful joyfully proclaimed, “Christ is risen!” It was Pascha, and the grace of the Resurrection flooded our humble chapel. Betty Rice was experiencing the service for her first time as an Orthodox Christian, and something was moving her in a mighty way. Her life, her family, and her community had known great suffering. Pain, loss, violence, strain, and many traumas were the backdrop for her journey to Holy Orthodoxy, but on this night everything was different. To be in the mystical presence of the risen Lord Jesus, to receive Him in a way that sealed the grace of the Resurrection on her heart, was otherworldly. Something was healed for her that night.

Betty is African American. I can remember meeting her in the early days of my ministry with what is now the Neighborhood Resilience Project, based in the Hill District, a predominantly Black community in Pittsburgh. Rooted in the Gospel and the teachings of the Orthodox Church, and inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, the Neighborhood Resilience Project aims to help transform trauma-affected communities into resilient, healthy ones. I was blessed to establish this ministry in 2018—two years after I had begun serving at a new mission parish in the Hill District, St. Moses the Black. At that time, I assumed many elements of Orthodox worship, like the icons, would seem foreign to most people in the neighborhood. But as it turned out, our traditions often spoke to them in a way I didn’t anticipate.

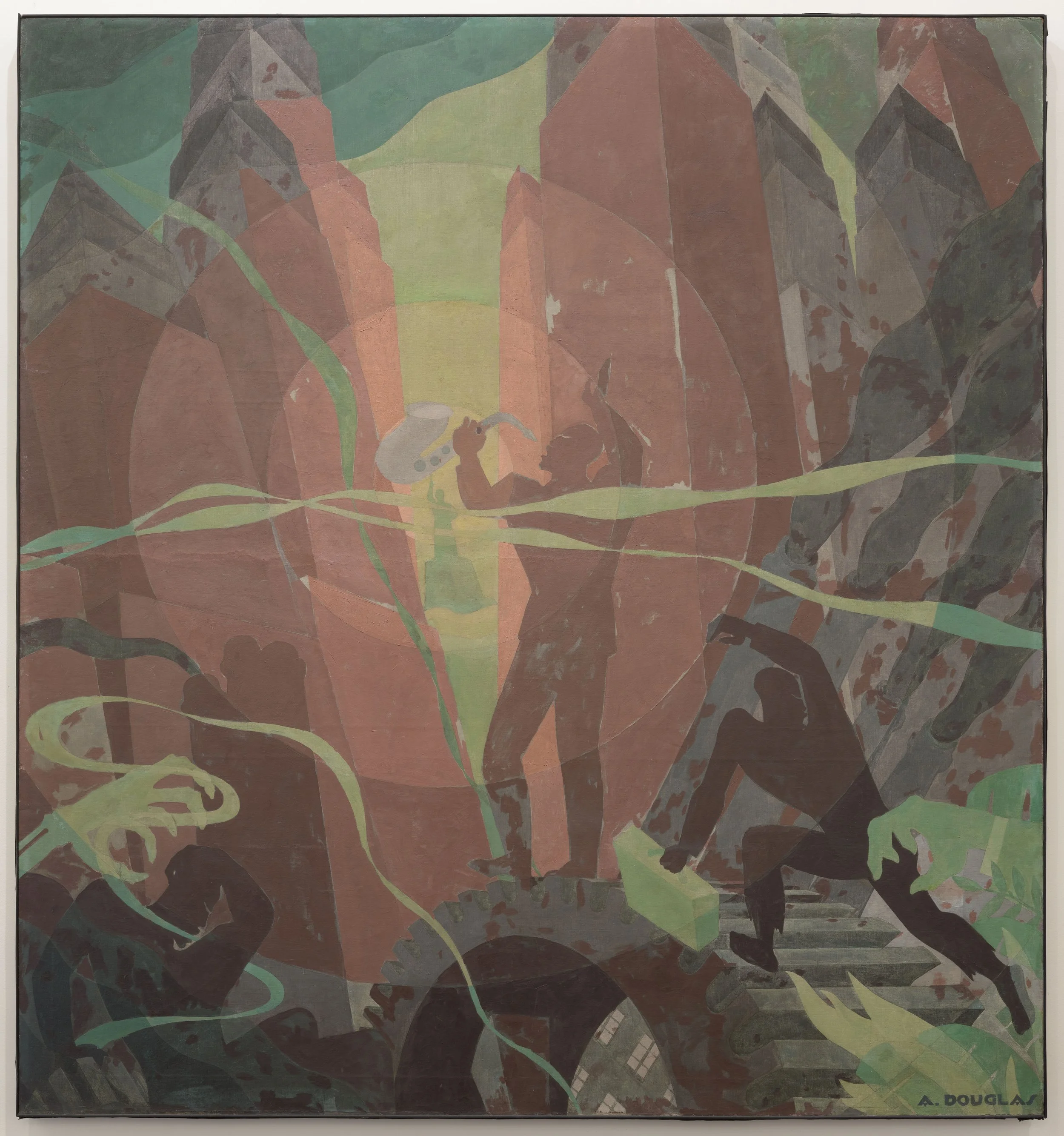

On another day, for instance, I had a visit from an African American woman whose teenage grandson had been murdered on the steps of his house, two doors down from her. In a moment of anguish over the trial of her grandson’s alleged killers, she stood outside my office, peering into an icon of the Transfiguration. After looking intently, even longingly, at this icon for a long while, contemplating the unbearable pain in her heart, she said to me, “Father, I have many questions for God about everything that happened. I was so confused, so uncertain, so wounded. But something amazing just happened right now. I stared into this icon, and somehow, some way, God answered me. I stared into this icon and found God’s peace. Somehow, in this icon, God answered every question I had.”

Many other visitors to St. Moses and the Neighborhood Resilience Project have expressed similar thoughts. It has often seemed that the people of this community, in some mystical way, recognize Orthodox Christianity. They respond not only to the icons, but also to the prayers, the incense, and even the sacred music. I can remember when one African American woman who had also become Orthodox brought her older father to the Divine Liturgy for the first time. In the middle of the Liturgy, she leaned over to him and said, OK Dad, I just want to prepare you because this church music is different from what you are used to. Annoyed by her comment, he responded, Don’t talk to me like I don’t know this music. This is like what we used to sing a long time ago.

I believe the explanation for this has deep historical roots. When we think about the development of Christianity in the U.S., it’s important to understand that for African Americans the faith took hold in a radically different context than it did for most other racial and ethnic groups. Whereas many journeys to America began in pursuit of a better life, the journey for African Americans began with excruciating pain and unspeakable horror. The transatlantic slave trade tore millions of Africans from their families, enslaving them in most brutal conditions. Many Africans didn’t even survive the terror of the slave ships. And for those who did arrive on American shores, their new lives were often characterized by beatings, rape, starvation, murder, and radical isolation.

The testimony of one survivor of slavery, Ottobah Cugoano, is worth quoting here. Cugoano was born in West Africa in 1757 and was captured for the slave trade as a young child. He wound up in the Caribbean and was later taken to London by a merchant. After he was freed, he joined in the cause of abolition. In his 1787 autobiographical pamphlet, Cugoano describes the terrors he experienced as a young boy:

I was thus lost to my dear indulgent parents and relations, and they to me. All my help was cries and tears, and these could not avail; nor suffered long, till one succeeding woe, and dread, swelled up another. Brought from a state of innocence and freedom, and, in a barbarous and cruel manner, conveyed to a state of horror and slavery … And yet it is still grievous to think that thousands more have suffered in similar and greater distress, under the hands of barbarous robbers, and merciless taskmasters; and that many even now are suffering in all the extreme bitterness of grief and woe, that no language can describe the cries of some, and the sight of their misery, may be seen and heard afar; but the deep sounding groans of thousands, and the great sadness of their misery and woe, under the heavy load of oppressions and calamities inflicted upon them, are such as can only be distinctly known to the ears of Jehovah Sabaoth.

It was not hope, nor joy, nor excitement, nor eagerness that characterized the African journey to America during the transatlantic slave trade, but rather, it was pain of the heart. This pain became the origin of an agonizing prayer, the prayer of broken hearts, which—in the words of Cugoano—“can only be distinctly known to Jehovah Sabaoth.” This was a collective cry to the heavens, beseeching an almighty God for His mercy and compassion.

His words resonate with a description of prayer from St. Paisios the Athonite, which appears in the second volume of the saint’s collected spiritual teachings:

Real prayer begins from pain; it is not a pleasant experience, a ‘nirvana.’ What kind of pain is it? One is troubled in the good sense of the term. He feels pain, he groans, he suffers when praying for anything whatsoever. Do you know what it means to suffer? Yes, he suffers, because he is participating in everyone’s pain or in the pain of one particular person. This participation, this pain is rewarded by God with divine exaltation. Of course, he doesn’t ask for this exaltation, but it comes as a consequence, because he participates in the pain of others.

In the sea of unrelenting pain which poured forth from African hearts in violent bondage in the Americas, real prayer was born. The world had betrayed and forsaken these beautiful souls who now had no ignorance or naïveté regarding the perverse character of this fallen world. For these enslaved Africans and their descendants, their cries, unheard by men, became prayers heard by God.

These circumstances opened a path for profound encounters with the living God. Slaves cried out in sheer agony to heaven, and our Lord Jesus Christ was the God that visited them. There was this deep sense that Christ had revealed Himself as a God of mercy, and this spurred a desire to reject this world and look heavenward. There was an abiding sense that when crying out in the hour of pain, prayers were heard by the Lord. In His presence, the worshipers became free in a different way; free from this world, becoming instead children of God and citizens of the Kingdom.

Consider the account of Anderson Edwards, which appears in the landmark book Slave Religion, by the Orthodox Christian and African American scholar Dr. Al Raboteau (of blessed memory):

We prayed a lot to be free and the Lord done heered us. We didn’t have no song books and the Lord done give us our songs when we sing them at night it jus’ whispering so nobody hear us. One went like this:

My knee bones am aching,

My body’s rackin’ with pain,

I ‘lieve I’m a chile of God,

And this ain’t my home,

‘Cause Heaven’s my aim.

Generations after slavery, this faith can still be found among African Americans in 21st-century America. Although slavery ended in 1865, suffering for Blacks in the United States did not. The Jim Crow era lasted for another century and took many forms of expression, some of them brutal. Take the policy of redlining, for instance, which was imposed by the Federal Housing Authority in 1934 to ensure no investments would be made in predominantly Black communities to support home ownership and business development. Let us also remember the hundreds of thousands of African American lives that have been claimed by gun violence over the decades, as well as the disproportionately high infant and maternal mortality rates among Black Americans. All this is to say that pain has remained familiar to African Americans up to the present day. Despite this being the case—or maybe more accurately, because this is the case—a humble and mighty prayer is still to be found deep in the African American heart. It is that brokenhearted cry to Jesus that our suffering ancestors taught us, which for many continues to be the center of life.

This is the prayer that is now leading many African Americans to the Orthodox Church. That deep tradition of sorrowful joy to be found in the Church of the Apostles is like a beacon guiding the brokenhearted home to the ancient Church. It is by the Cross that the Lord draws all people to Himself (Jn 12:32), and it is indeed by the cross that many African Americans have been drawn to Christ in Holy Orthodoxy. It is in the Orthodox Church that the mystery of the Cross is experienced in its fullness.

That old spiritual that our ancestors sang, “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?,” takes on new meaning when we experience the mystery of anamnesis in the liturgical life of the Holy Orthodox Church—whereby we remember through mystical participation in the Life of Christ. The Orthodox Christian who has encountered the Lord in the divine services of the Orthodox Church is able to answer the poignant old Black voice, “Yes, I was there.” More important, however, it is the Orthodox Christian who can perhaps more profoundly respond, “Were you there when my Lord rose from the dead?”

“Christ is risen!” That Paschal proclamation written on the heart of every right-believing Orthodox Christian now completes the revelation painfully begun long ago with the cross that many poor enslaved African persons bore long ago. It is the pain of the Cross that is now transfigured by the risen Lord Jesus Christ, who promises, “Most assuredly, I say to you that you will weep and lament, but the world will rejoice; and you will be sorrowful, but your sorrow will be turned into joy” (Jn 16:20).

Returning to Betty, who stood in the church weeping that Holy Pascha night, something had happened. She knew the Cross well. Both her son and grandson had been shot down senselessly in the streets. After these murders, an unspeakable pain gripped her heart. There were days when it was difficult for her to even get out of bed. This loss was more than she could bear, and it seemed that she had not only lost her son and grandson, but also that they had lost their mother and grandmother too.

That Pascha, however, everything had changed. “Come, receive the Light!” the priest chanted as the royal doors of the altar were opened. “Christ is risen!” She heard these words for the first time as an Orthodox Christian, and she now knew she was finally in the presence of the risen Lord Jesus Christ. Yes, she was there when He was crucified, but now she was finally there in His Resurrection. Later, at the end of the service, as I stood offering a Paschal greeting to parishioners, Betty approached me, sobbing, and gave me a hug. “Tonight,” she said, “my son got his mother back.” She felt alive for the first time in decades.

Her experience, and many like it, seem to be the fulfillment of everything our suffering ancestors of African descent told us was possible. It is this fulfillment that I believe is now drawing many of African descent into the Holy Orthodox Church. In this context and heritage, Orthodox Christianity is not foreign or strange, but rather familiar, comforting, and liberating.

Betty later established a group called Healing Your Heart, which ministers to other women who have lost their children and loved ones to gun violence. She now comforts women, entering into their pain with prayer and thanksgiving. What began as she partook of the Eucharist has now poured out into the streets and living rooms where brokenhearted women are found in great numbers. We can’t just stay in our church now, Father, she has told me. We have to go out into the streets, making some kind of great procession. We’ve got to walk the streets praying, Father! We need to go out into the community and bring all heaven down to earth!

That’s what she experienced that Holy Pascha night: In hearing “Christ is risen!” in that eucharistic context, she experienced all of heaven coming down to earth. Now she wanted that for her entire community. Through people like her, the faith of the apostles continues to spread in a mighty way among a suffering people.